I think it is somewhat more complicated than this because of the yield curve. Taking the example of a 4% coupon callable at 3 years and maturing in 23 years - if the price goes above par, then the yield will be compared against other 3 year bonds, while if the price is below par then it will be compared against other 23 year bonds.Good riposte--the effect is not very visible when the price is near par. Try it again at 90 / 110, or better, 120 / 80, you'll see a more dramatic effect for the contraction in maturity when priced to call.I don't think this is right. If a bond has a coupon of 4.0%, has 3 years to (par) call, 23 to maturity, and is currently trading at 100.5, it will have a yield of just under 4.0%, based on yield to call. If it drops by 1 point, to 99.5, then it will be priced on yield to maturity, which will be just over 4.0%. The transition in *yield* based on that 1 point swing will be small.Compilers should be aware that the convention in secondary sources, such as the Federal Reserve bulletins, was to compute yield to call if the bond sold above par (making it a candidate for call), and yield to maturity if selling below par. That yield could change by a lot in a day, if the bond rose or fell by a single point, bringing it above or below par.

On the other hand, the transition in expected duration (depending on the method used) could be quite sharp, from just under 3, to something much longer (19ish, maybe (guesstimating)?)

===

That said, yes, it's rather significant that treasuries were generally callable as late as through the mid 1980s. (I did not know this - thanks for the history.)

Given a callable bond and a non-callable, both with a 5% coupon, a price of 99.5, and ~25 years to maturity (but only, say, 5 years to call for the callable), then the callable bond is strictly worse for the investor, by a significant margin. Given stagnant yields, then yeah, maybe it doesn't get called and effectively they produce the same cash flows. But yields may go down, which benefits the callable bond much less than it benefits the non-callable. There's maybe no good way to portray this in a long series of extrapolated "10 year treasury yields", but in the real world, it matters, modestly lowering the attractiveness of government bonds during the callable time frame, and modestly increasing the equity risk premium, in effect.

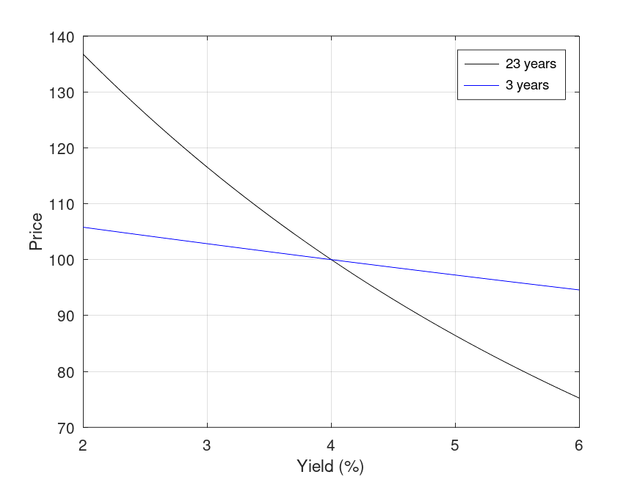

The following figure shows the price as a function of yield for our example 4% bond callable at 3 years and maturing in 23 years

When the price is above par, it will follow the 3 year line and when the price is below par it will follow the 23 year line.

Imagine the case where the yield at 23 years starts at 4.5% and falls to 3.5% while the yield at 3 years is a constant 1.5 percentage points below this and, therefore, falls from 3% to 2%. The bond price starts at about 93 and increases to 100 when yields have fallen to 4%. A further decrease in yields at 23 years to 3.5% will increase the price above par and therefore it will now follow the blue line, but the yield is now 2% (not 3.5%) because it has switched to the 3 year line and so the price is about 107. Assuming an efficient market, there will actually be a step in price as the yield goes through 4% at 23 years to 3% at 3 years from 100 to 103. The step will be larger for a stronger gradient in the yield curve. How the market priced them when the yield curve was inverted such that the yield was above the coupon for 3 years and below the coupon for 23 years is beyond my knowledge.

I had the (dubious) pleasure of calculating index returns for the UK using prices, coupons, and maturities. As well as dealing with this aspect of pricing (which is relatively trivial given the call and maturity dates), for indices with fixed maturity ranges (e.g., bonds with maturities of 5 to 10 years), callable bonds can also join and leave the index as the yield flips above and below the coupon rate making tracking the returns awkward (while I had monthly data, I note that the membership of the FTSE indices is determined on a daily basis - thankfully, the UK no longer issues callable gilts).

cheers

StillGoing

ps I should also note that UK Consols while sometimes known as perpetuals or irredeemables were often callable (usually a substantial time after issue) and were, eventually, definitely redeemable (it is nearly a decade since the last was redeemed). A useful detailed history on individual gilts can be found in Pember and Boyle linked at https://www.escoe.ac.uk/research/histor ... scal-data/ (under periodicals).

Statistics: Posted by StillGoing — Mon Aug 05, 2024 3:55 am